Rufino Varea and Faaimata Havea Hiliau spoke on board the Uto ni Yalo. (Ben McKay/AAP PHOTOS)

On the sidelines of the frenetic Pacific Islands Forum Leaders Meeting this week, there was calm.

Moored on the Nuku’alofa wharf was a boat – the Uto ni Yalo – built both to honour and in the style of the great Pacific seafarers of centuries past.

Its crew had sailed from Fiji, a seven-day voyage given unkind winds, for a different sort of climate protest.

Not to stop traffic, march on streets, hunger strike or vandalise.

Their protest was the success of the journey, to travel using old ways, to show it was possible – and that it could inspire.

“It is a gentle but powerful reminder of what our ancestors, our forefathers, were able to achieve without fossil fuels to navigate our ocean, vast ocean,” Rufino Varea, a climate activist from the Fijian island of Rotuma said.

Mr Varea climbed on board the Uto ni Yalo – meaning ‘Heart of the Spirit’ – for a First Nations dialogue held alongside the Pacific summit.

The dialogue was staged as a talanoa, a Pacific style of respectfully thrashing out differences, while seated on a traditional mat, with kava on stand-by.

Participants had different backgrounds from across the Pacific, but all held the same horror at the spiralling climate crisis.

“We recall the fires and floods that have wreaked havoc and taken lives in Australia over the last few years,” Uniting Church NSW moderator Faaimata Havea Hiliau said, on behalf of Queensland First Nations woman Cathy Eatock.

“We see Central Australia communities become almost unlivable, suffering 55 days over 40 degrees in recent years.

“Our Torres Strait Island communities are suffering the same fate as many to Pacific islands. Our houses flooded, our cemeteries being washed away and salt water contaminating drinking water.

“It’s not some vague future threat. It’s here right now.”

The talanoa felt a world away from the action of the PIF meeting in Nuku’alofa.

With more than 1600 accredited visitors, this was the biggest summit ever hosted in the Tongan capital, which buzzed with activity from the heavyweights and their hangers-on.

All but one of the 18 PIF members was represented by their leader, all with plenty of supporting officials.

Greater powers like the United States, China, the European Union, France, Germany, and other “dialogue partners”, brought delegations. Countries further abroad, like Uganda and Ghana, did too. Smaller nations sent ambassadors.

The United Nations Secretary General and his cohort travelled through, along with other international agencies.

All were shuffling back and forth between venues – in a motorcade if they were lucky – including the Tonga High School stadium and the Tanoa International Dateline Hotel on the waterfront, the fanciest hotel in town.

Meanwhile, the Uto ni Yalo bobbed peacefully in the Pacific.

Those on board were aware of the dissonance between the helter-skelter summit and their quiet discussion.

The same dissonance exists between the policy prescription to curb climate change, and the action being taken.

As scientists, civil society organisations and the United Nations call for a handbrake on fossil fuel extraction, developed countries approve new mines and explore for new gas fields.

“All this puts Pacific Island nations in grave danger,” UN Secretary General Antonio Guterres said while in Nuku’alofa.

“This is a crazy situation.

“Rising seas are a crisis entirely of humanity’s making, a crisis that will soon swell to an almost unimaginable scale, with no lifeboat to take us back to safety.”

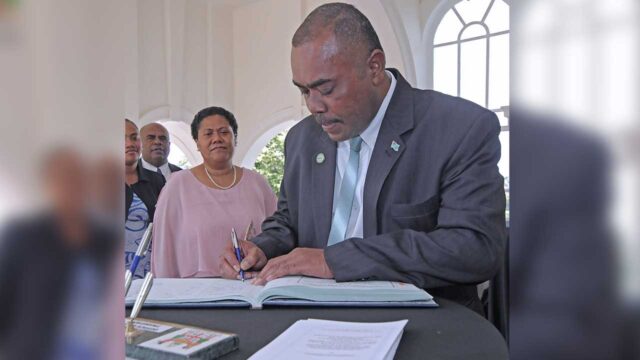

Tuvalu Climate Change Minister Maina Talia – whose government celebrated a security and climate pact with Australia, the Falepili Union, just as day earlier across town – spoke from the mat with fury.

“Fossil fuels are killing us, all of us. Opening and subsidising and exporting fossil fuel is immoral and unacceptable,” he said.

Talanoa participants were also united at the prospect of Australian assistance.

“It’s clear from the statements we have heard that we cannot rely on big countries like Australia to help us,” Mr Varea said.

While in Tonga, Anthony Albanese pointed to Australia’s emissions reductions targets as proof of his country’s commitment.

However, Australia’s ongoing approvals to coal mines, its huge production – and taxpayer-funded subsidisations – of natural gas, set to continue for decades, shows the limit of Australia’s responsibility.

“When we call on nations like Australia and New Zealand to do something about their climate change policies, it almost feels like we are not heard,” Fe’iloakitau Kaho Tevi, a Tongan elder, said.

“Like we are talking to a wall, just a bunch of cement blocks.

“The sense from within the Pacific Island countries is let’s start to do what we can do.

“Let’s do our part, and let’s build resilience from within, from within our people, from within our traditions.

“Let’s go back to what we know best, and let’s leave the way we live that we know best.”

Another dissonance existed in Tonga this week – the climate peril faced by Pacific leaders and the unwillingness from those same leaders to call out directly the leaders of the region’s biggest polluters.

‘Alopi Latukefu, director of the Edmund Rice Centre, suggested there should be a limit to the deference offered from the Pacific.

“Sometimes not saying anything is as much a way of saying something,” he said.

“On this issue perhaps there needs to be more forthright discussion from Pacific and Pacific leaders directly to Australia and New Zealand.”