The successful implementation of a Truth and Reconciliation Commission hinges on the government’s commitment to adopting and acting upon its recommendations.

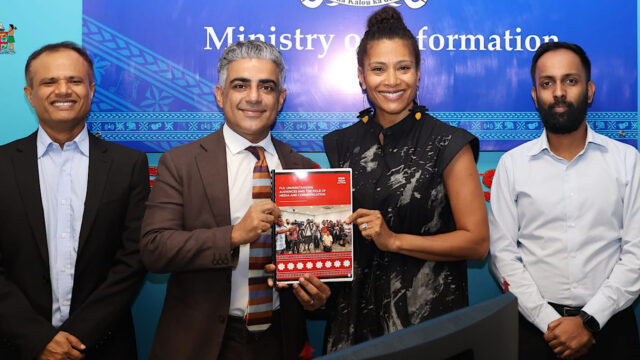

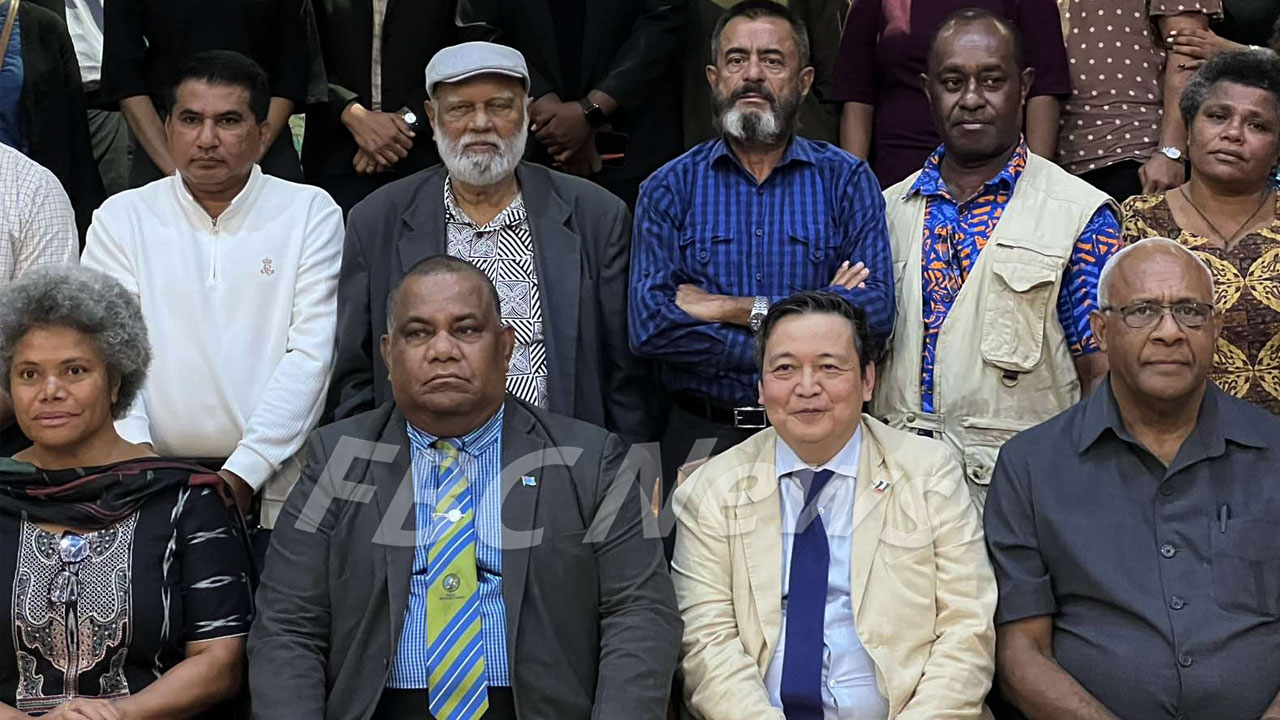

This was highlighted during the public consultation on the establishment of the Commission at the Suva Civic Center this morning.

A question on how such commissions operate in post-conflict societies was posed to a Senior expert at the International Center for Transitional Justice Ruben Carranza.

He states that the value of a Truth Commission lies not just in its report but in the government’s willingness to engage with and address the issues it uncovers.

He explained that it is a temporary State body tasked with addressing a history of violence and injustice.

As such, its success cannot be easily measured by traditional standards.

“Well, how would a Fiji Truth Commission work? I don’t know.”

It hasn’t happened yet. So a lot of it requires some flexibility, and so measuring success from the donor perspective, I would ask donors to consider that. This is not an ombudsman’s office.

“This is not a Human Rights Commission. This is not some NGO. This is a singular, temporary state body that’s addressing a long period of violence in the past. Now, that’s the donor-driven answer, but really, I think the success in this case is almost impossible to measure.”

Carranza reflected on the case of the Solomon Islands where the Truth Commission’s report was withheld by the government for several years before finally being released.

This delay, he says underlines the critical role of government action in ensuring that the findings and recommendations of a Truth Commission are not just acknowledged but also implemented.

The release of the report, though delayed was a crucial step toward healing and reconciliation.

The discussions this morning also touched on the challenges of integrating Truth Commission findings into national education systems.

Carranza cited examples from South Africa and Kenya, where efforts to incorporate the commissions’ reports into school curricula faced significant obstacles.

In South Africa, despite the Truth Commission’s recommendations on reforming the educational system, many were not implemented, leading to continued unrest among university students.

Similarly, in Kenya, the government flatly refused to include the Truth Commission’s recommendations in the national curriculum.

Carranza pointed out that while some countries have successfully integrated Truth Commission reports into educational materials such as in Sierra Leone with a comic book summary or in Peru with translations into indigenous languages, these are exceptions rather than the rule.

The effectiveness of these efforts, he says often depends on the post-Truth Commission government’s willingness to use the recommendations and integrate them into broader frameworks including education.

Carranza reiterates that a Truth Commission’s work does not end with the publication of its report.

Its success, he says depends on the subsequent actions of the government particularly in adopting and implementing the commission’s recommendations.

Without this commitment, Carranza believes that the potential for lasting peace and reconciliation remains unrealized and the wounds of the past may never fully heal.

Stream the best of Fiji on VITI+. Anytime. Anywhere.

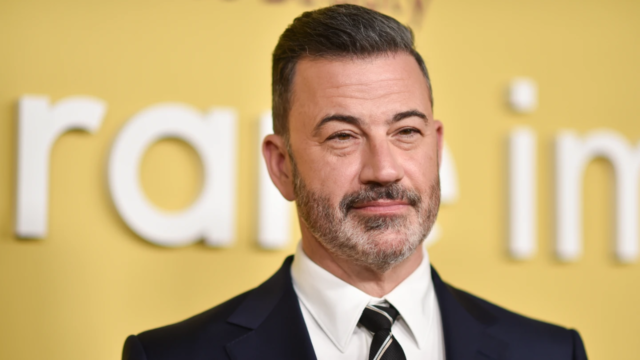

Litia Cava

Litia Cava