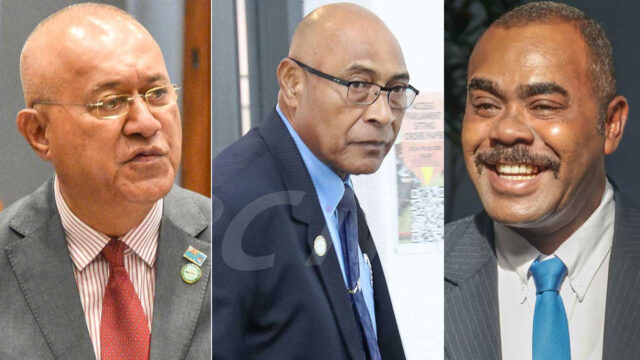

his image released by Warner Bros. Pictures shows Salma Hayek, left, and Channing Tatum in a scene from "Magic Mike's Last Dance." [Source: AP Entertainment]

The words Magic Mike may conjure up images of sweaty, sculpted, undulating men, dancing unthreateningly for hoards of screaming women, but there has always been a backdrop of brutal economic reality looming over the fantasy world.

The unlikely franchise has explored the escalating devaluation of physical labourers, the suffocating effects of the college industrial complex, predatory loan businesses, the recession and even COVID-19, which has effectively destroyed poor Mike Lane’s furniture business in this latest film.

When we re-meet Channing Tatum’s gentle hunk in “ Magic Mike’s Last Dance,” in theatres Friday, he’s bartending at parties for the very rich in Miami. The gig could be worse, but though he doesn’t quite say it, the implication is that he’s even aged out of dancing now. He has to seriously think about it when his wealthy employer offers him $6,000 for a dance later that evening.

Asking why sequels exist doesn’t usually produce satisfying answers, but “Magic Mike’s Last Dance” is a film that was born backwards, a fit of inspiration from Steven Soderbergh after seeing what Tatum had done with Magic Mike Live. The Las Vegas stage show, inspired by the first two movies, is described on its website as “an unforgettably fun night of sizzling, 360-degree entertainment,” “hot,” “hilarious,” “the great time you’ve been looking for” and “the ultimate girl’s night out.”

But “Magic Mike’s Last Dance” is not quite any of those things and perhaps might even annoy some of its most enthusiastic fans — the ones who simply want to holler at the six-packs in front of them. Because this film is that thing that many sequels promise but doesn’t deliver on: It’s both a true evolution and a conclusion. It’s also part fantasy, part bleak reality, part commentary on the fundamental value of dance and what’s lost in a society that has forgotten how. It is not, in other words, simply another striptease.

“Magic Mike” and “XXL” (directed by Gregory Jacobs) both latched on to a kind of pure joy in the spectacle of the male stripper. But that audience, by nature of its venues, is inherently limited and “down market.” In “Last Dance,” Soderbergh gives Mike a wealthy benefactor, in the form of the operatically named Maxandra Mendoza (Salma Hayek) who is in the midst of a messy divorce from an obscenely successful media mogul and looking to shake things up.

After an acrobatic, but fully clothed, encounter with Mike, she decides to whisk him away to London, dress him up and put him in charge of staging a show that promises to make its audiences feel the way she did the night she met Mike. In the process, she, Soderbergh, Tatum and screenwriter Reid Carolin, set a historic London theatre, and all of its fussy rules, ablaze (figuratively). If only all scorned socialites could do something so charitable with their rage.

It’s a clever conceit for a filmmaker who never tires of singeing the establishment he continues work in. And like many Soderbergh films, “Magic Mike’s Last Dance,” shaggy, earnest and innocently tawdry, goes down so easy that it’s almost impossible to appreciate it fully on a first watch. I imagine it will only improve with more.

If there is a quibble, it’s that Hayek and Tatum don’t quite inspire the will-they-won’t-they tension that the movie seems to be asking of them. They work well together when they’re working together, but the romantic chemistry is a bit lacking. Besides, his great unrequited love isn’t a person but his furniture business, right? It doesn’t help that Maxandra is also an extremely underdeveloped character.

Even so, Mike manages to wrest an inspired dance in the rain out of the idea of them (his co-dancer is Kylie Shea) that pays homages to classic movie musicals with just a bit more skin and writhing.

This story is told like a fairy tale, or a poetically composed school paper from a particularly precocious student, with a silky-voiced young narrator telling us about Mike’s woes and the waning significance of dance in the culture. She’s not just a disembodied voice, but an important character the story reveals later. But it’s a lovely little flourish in Mike Lane’s journey. He’s a guy who just wants to make furniture but seems destined (or doomed) to continue performing in one way or another. Like his director, he’s just too good at it to say goodbye forever, no matter how much they both keep trying.

Associated Press

Associated Press