[Source: Reuters]

About 76 million years ago, a juvenile of one of the largest flying creatures in Earth’s history, called Cryodrakon boreas, walked along a riverbank on a lush coastal plain and lowered its toothless beak to take a drink, unaware of danger lurking at the water’s edge.

Suddenly, a large croc surged out of the water in an ambush and sank its teeth into the Cryodrakon’s neck.

That was life – and death – in the Cretaceous Period in the Canadian province of Alberta.

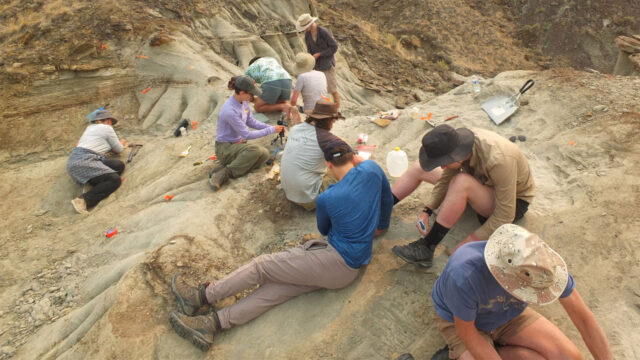

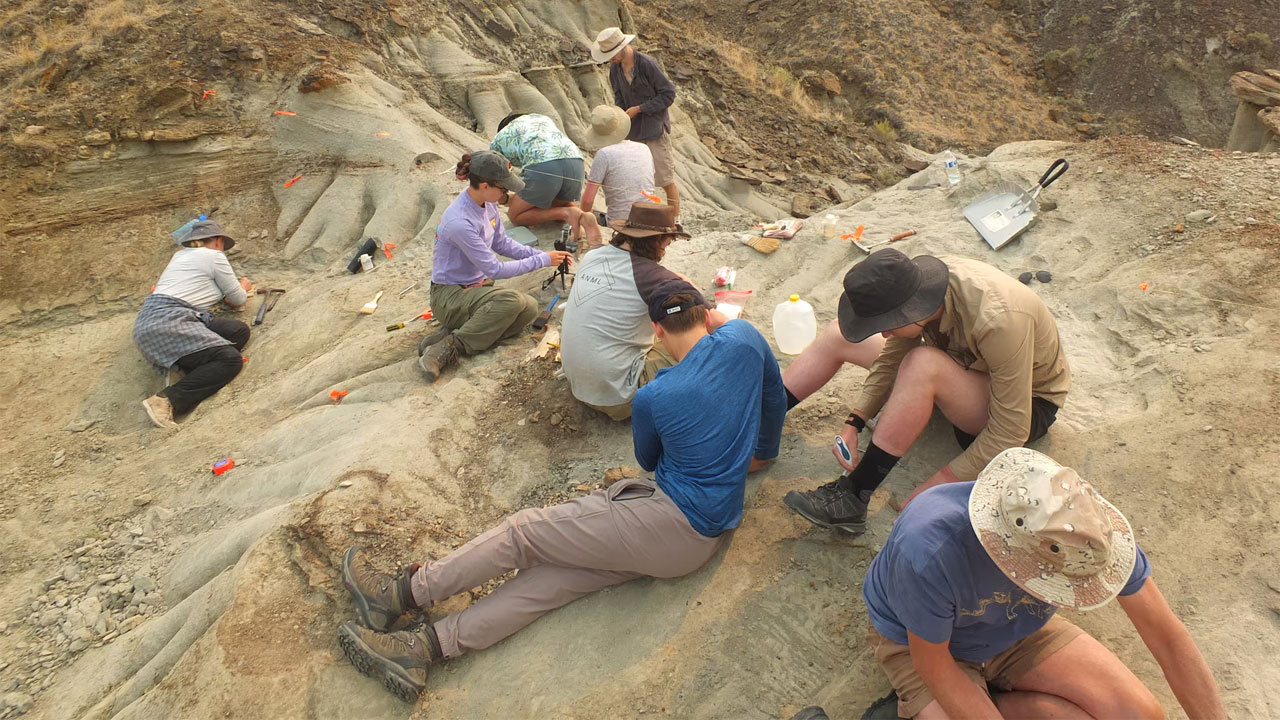

Scientists have unearthed in the badlands of Alberta’s Dinosaur Provincial Park the fossilized neck bone of a young Cryodrakon, a type of flying reptile called a pterosaur, that may have died in just such a scenario.

The fossil, examined under a microscope and with micro-CT scans, has a conical puncture a sixth of an inch (4 mm) wide that appears to be the bite mark of a crocodilian that either preyed on the Cryodrakon while alive or scavenged its body after death.

Adults of this pterosaur, whose scientific name means “cold dragon of the north wind” in reference to Alberta’s chilly modern-day climate, had wingspans of about 33 feet (10 meters) and stood as tall as a giraffe.

The juvenile’s wingspan was about 7 feet (2 meters).

The elongated neck bone, about two-thirds complete, is 2-1/4 inches (58 mm) long.

The bone is thin.

Much of its outer wall is less than a credit card in thickness.

“Most crocodilians feed at the surface of the water and are ambush predators, and many pterosaur species are thought to be tied to the water as well. Given this, if it was predation, it likely happened as an ambush at the water surface,” said paleontologist Caleb Brown of the Royal Tyrrell Museum of Palaeontology in Alberta, lead author of the study published this week in the Journal of Paleontology.

“The are several reasons why a pterosaur would be at the water surface, including drinking and hunting for food itself,” Brown added.

Modern crocs are both active predators and scavengers.

“There is no sign of healing, so the wound either happened at the time of death during an attack or after the animal was already dead,” said ecologist and study co-author Brian Pickles of the University of Reading in England.

Cryodrakon rivaled Quetzalcoatlus, which also inhabited North America at the time, as the largest of the pterosaurs, which were cousins of the dinosaurs.

Both had large heads with large toothless beaks, long necks and short tails.

“They were carnivorous, but researchers have disagreed as to their feeding strategy – with suggestions from carrion-feeding scavengers to aquatic probers to heron-like terrestrial stalkers,” Brown said.

The researchers noted that the puncture mark does not match the shape of the teeth of dinosaur predators in this region at the time, such as the Tyrannosaurus relatives Gorgosaurus and Daspletosaurus. Instead, it matched the shape of a croc’s tooth.

Crocodilians living in this ecosystem included Leidyosuchus, around 12 feet (3.5 meters) long, and the smaller Albertochampsa.

The semiaquatic superficially croc-like Champsosaurus also was present.

This was a warm, wet and flat ecosystem, bisected by large rivers.

There were duck-billed dinosaurs, horned dinosaurs, armored dinosaurs, meat-eating dinosaurs, and various crocs, turtles, small mammals, birds, amphibians and fish.

Scientists actually have more data on the animals that ate Cryodrakon and its closest relatives than what it ate.

Another Cryodrakon specimen from Dinosaur Provincial Park has tooth marks and an embedded tooth from the meat-eating dinosaur Saurornitholestes.

The bone of a Cryodrakon relative was found in the stomach remains of a Velociraptor from Mongolia. Another one from Romania has what might also be croc bite marks.

Despite their sometimes gigantic size, pterosaurs are less well understood than dinosaurs because their bones are thin and delicate, making them less apt to be preserved as fossils.

“Direct evidence for ecological interactions like this fossil help define the ecological role of these really mysterious animals,” Brown said.

Reuters

Reuters