[Source: Reuters]

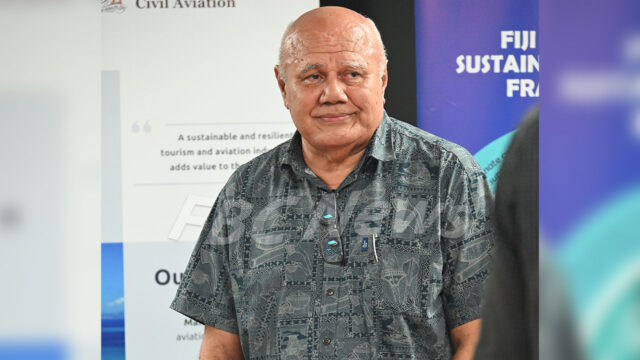

For pub owner Jun Jung-sook, Seoul’s once-vibrant Nokdu Street is not what it used to be when people queued for a table to end their day with Korean mung bean pancakes and shots of the fiery local rice wine makgeolli.

The more common sight now is of half-empty pubs and bars along the neon-lit alley and streets, a telling sign of a sharp shift in South Korea’s once-notorious drinking culture.

That change has been driven by corporate Korea slowing down on hoesik, or after-work drinking bouts, the emergence of an emboldened class of younger female workers who are refusing to be part of these drunken sessions and a general reluctance of consumers to open their wallets due to higher interest rates and lingering inflation.

The consumption downturn has dealt a major blow to popular second-round places like Jun’s and reflects a broader slowdown in domestic demand in Asia’s fourth-largest economy which barely grew in the third quarter.

It also underlines the challenges facing South Korean businesses from Noraebangs, or singing rooms, to retail rents and mom-and-pop pubs.

“I don’t see anyone drunk anymore. The streets here used to be packed…that’s long gone,” said Jun, 77, glancing over an empty hallway that once bustled with people playing drinking games such as one on APT, the latest K-pop hit by ROSE.

While elevated borrowing costs remain a dampener on consumers generally, the fast disappearing mom-and-pop beer halls like Jun’s that point to a shift in South Korea’s hard-drinking culture suggests other more enduring forces are at play.

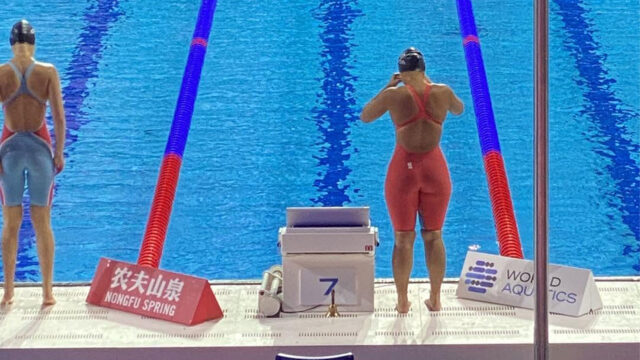

The rise of a health-conscious younger generation across the region is one key factor.

In neighbouring Japan, for instance, increased health awareness and the flexible working style brought about by the pandemic have also led to a decline in their alcohol consumption, according to a survey by Euromonitor.

At home, in the years following a 2007 ruling by the Seoul High Court that deemed it an offence to force subordinates to drink alcohol, an increasing number of women have started to complain about hoesik as it takes time away from childcare and due to the risk of sexual harassment.

Hailey Kim, a 40-year-old office worker at an auto parts company, attributes the fading of the after-work meal and drinks gatherings to the growing presence of younger and more outspoken women colleagues.

The introduction of an anti-graft law in 2016 which placed caps on meal expenses for public officials to weed out corruption is another contributory factor, she say.

“There used to be a pattern: starting with grilled pork, then a 2-cha (second round) at a beer place, followed by holding hands and singing at a Noraebang. We definitely don’t do that anymore, just stop at the barbecue, thank God.”

The numbers tell the story.

Alcohol consumption in South Korea has dropped 12% from a 2015 peak, the second fastest rate of decline among Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development nations.

An index measuring sales at local eateries was at a record low of 88.4 last year, according to latest available figures, while the number of Noraebangs decreased to 25,990 as of July this year from 28,758 in 2020, a trade association said.

Just an hour’s drive inland to Jongno reveals a troubling sight as retail streets surrounded by office buildings were dotted by shuttered shopfronts and for-lease signs on Noraebangs.

‘ALL DUTCH NOW’

South Korea has one of the world’s highest proportion of self-employed people, about 25% of the job market, far higher than the average of 15% among OECD countries, making it particularly vulnerable to downturns.

The fading nightlife scene and shuttered Noraebangs highlight a bigger problem for policymakers: how to address a disparity between solid exports and weak domestic consumption.

Robust external demand isn’t feeding into broader economic strength, complicating Bank of Korea’s quest to engineer a soft landing for the economy in the current rate-cutting cycle.

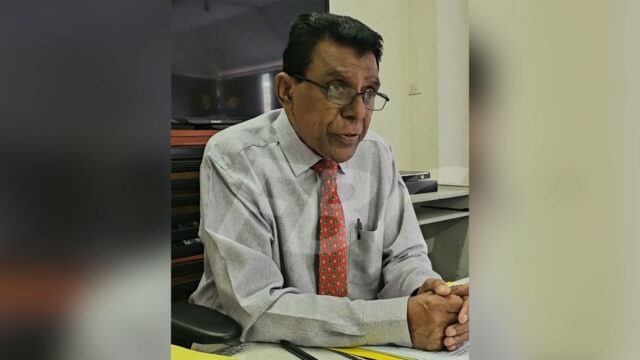

“Weaker domestic spending goes to show that people are less well off. Retail sales show consumers increasingly spend more money on convenience stores for takeaways and are cutting back on restaurants,” said Lee Jin-kook, an economist at the Korea Development Institute.

For Jun, slower consumption amid the changing drinking culture means letting go of her bindaeddeok place she has been running since 1993.

Her place has been put up for lease since 2022 but she hasn’t received a single offer.

“Some people used to pay for other tables just because they went to the same university, even if they are total strangers. That culture is gone, it’s all go-Dutch now,” Jun said, as the evening news on TV hummed in the background with North Korea’s latest missile launch.

Reuters

Reuters